Around the time that John and Alan Lomax were recording and preserving folk music in the Americas, Englishman Hugh Tracey was recording and archiving much of that music’s very roots in Africa.

Between the 1920s and the 1970s, Tracey recorded around 250 tribal groups. In 1954, he founded the International Library of African Music (ILAM) in Grahamstown, South Africa.

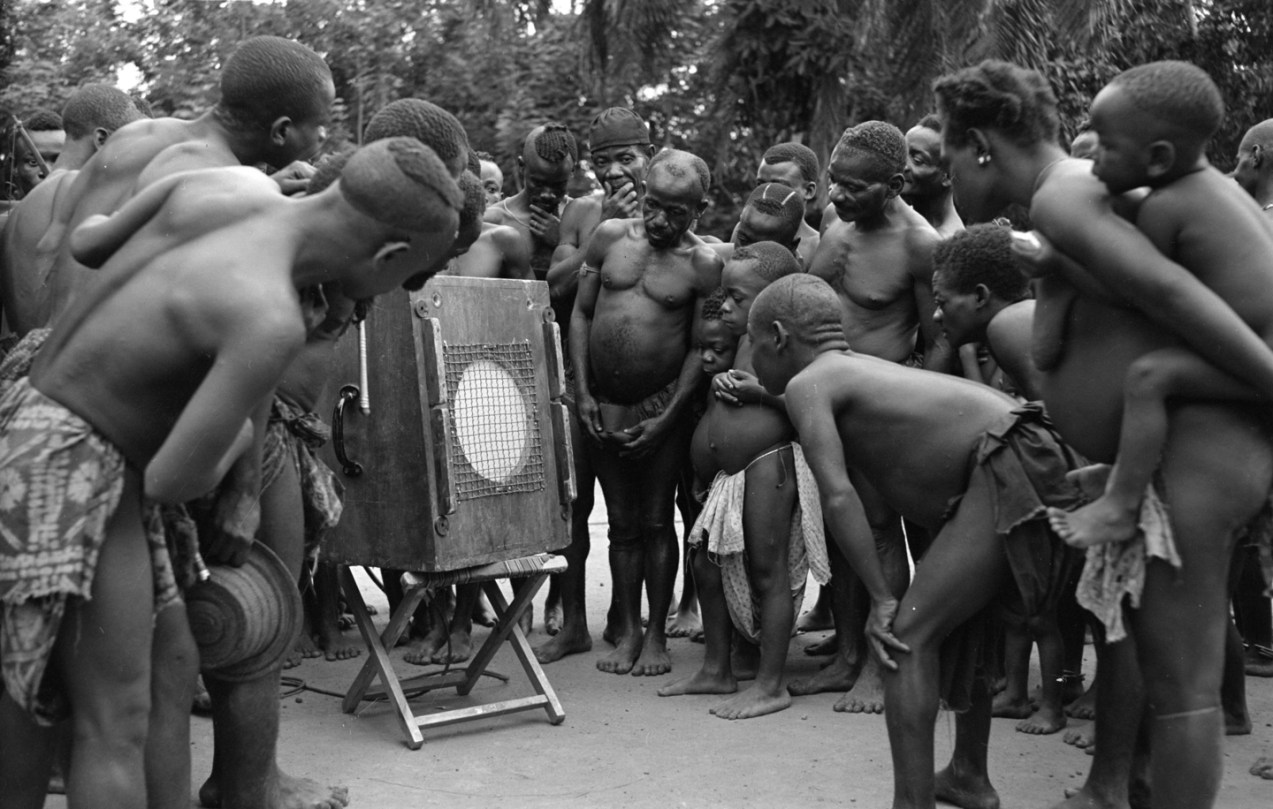

Sixty years later, another Englishman, musician Chris Pedley, discovered Tracey’s work after seeing a photograph in his future wife’s home. At the time, he didn’t know what to think, but he now knows it captured an Mbuti pygmy tribe in the Congo crowded around a speaker.

“I was intrigued; I thought ‘What is going on here?’” recalls Pedley. “My wife Lisa said, ‘Oh, my great uncle was an explorer in Africa who recorded music’.”

Fascinated, Pedley was soon off to Africa with the idea of making a documentary on Tracey’s work: “I went out to the archives to meet Hugh Tracey’s son [Andrew], who told me everything about his adventures and the different musics Hugh had been captivated by.”